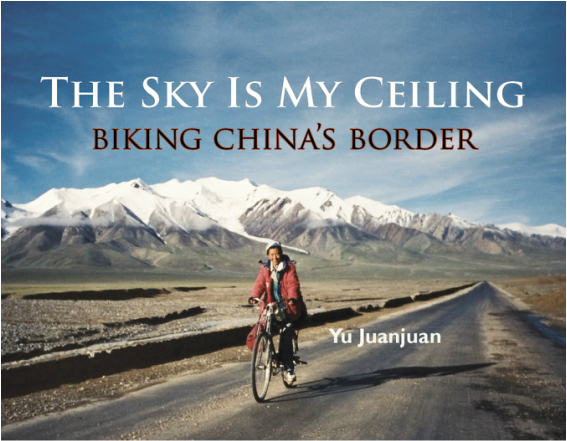

In December 2017 I published my first book, a memoir titled, The Sky is My Ceiling: Biking China's Border. The book tells the story of how I left on a twenty-two month bike journey in the fall of 1987 to bike around the border of China. I was the leader of a group of five bicyclists. It took me two years to travel over 40,000 kilometers, (25,000 miles) to complete this trip, the distance being equivalent to the circumference of the earth. The Sky is My Ceiling: Biking China's Border and its available for purchase for $23 USA and $28 Canadian. Please click on the button below to email me and purchase.

Introduction to The Sky Is My Ceiling: Biking China’s Border by Yu Juanjuan

by Sarah Massey-Warren

From September 1987 through July 1989, Yu Juanjuan bicycled around the border of China and in the process changed Chinese women’s history. Starting from Beijing with four team members, three dropped out early, leaving her with only one-team member, Wang. For the majority of the 22 month trip she faced most of the diverse challenges – the demanding terrain, the reaction from natives of cities and villages she visited, the wildly fluctuating weather, the need for funding, and those arising from the fact that she was a young woman – alone. Since then, nobody has been able to duplicate her feat, man or woman. The strength of this remarkable woman’s story– a product of the intersection of Communist and modern China – result in a compelling richly illustrated book documenting the enormity of her success.

To understand the trip, one needs to know the unique qualities residing in the woman behind the journey. Juanjuan’s determination in envisioning and accomplishing the trip derive from her family background and upbringing, her own education and work experience, and an insatiable quest to see beyond the constraints of her own city. Her own parents were educated, lived on a university campus in Beijing, and had an 18” television that let in the world to a limited extent during the Cultural Revolution. “We had no news and no ads,” Juanjuan recalls. A young woman when Mao declared, “women hold up half the sky,” she came of age at a time of great upheaval and cultural change. With a job of her own and with her family’s encouragement Juanjuan had a strong desire for a future destined to be bigger than her grandmother’s bound feet. “Everybody thought I was crazy, not a real Chinese person,” she says of the reaction to her announcement to bike around the vast expanses of China. “A young woman is supposed to focus on husband and family – it’s your duty.”

But Juanjuan’s adventurous family genetics ran through her muscles and memory. Her father, a medical doctor at the Beijing Normal University, believed in her: “You’re bigger than that”, he said and encouraged her athletic daughter’s achievements. In fact, the men in Juanjuan’s family bequeathed a lust for travel. One grandfather owned a bookstore filled with books and photographs of the wider world. The other, her father’s father, joined the “underground army” at age fourteen, which allowed him to traverse the country. Although her mother, who worked in the university’s student office, was more traditional, she remained emotionally and financially supportive of Juanjuan and even more so after the trip.

A natural athlete, Juanjuan ran marathons and biked extensively. However, what really built the muscles and endurance for the journey came from the Cultural Revolution edict of mandatory farm work required of university students. Juanjuan spent two years doing heavy labor on a rural farm. Others urban teens did 10 years of mandatory farm work and some never made it back to Beijing. “I did the work of two men by myself,” Juanjuan recalls. Returning to Beijing in 1976 after Mao died, jobs were plentiful and she landed an office job in the sports department of the China People’s University. The job had other advantages – she had summer months at her discretion to bicycle to other universities, take free classes and take long bike trips. During that time, these preliminary bike trips became increasingly longer, and triggered her appetite to explore China’s circumference and all that lay therein.

“I wanted to get to know different cultures and religions, different ways of living, different clothes, ladies my age and know their dreams! I love cooking – I wanted to taste and try different food. I wanted a grand adventure and a way to get to know China myself first hand.”

Fortunately for the reader, Juanjuan is a shutterbug and a star in her own photos. Continually, she asked people to take pictures of her, despite the expense incurred for film and development. She collected stamps from the local government and post office at each village she visited, which verified the validity of her travels and her identity to strangers. The photo-journalistic narrative of people, landscape, and stamps takes us from Beijing to remote villages and large towns. Through the textual travels and stunning images, we see all that Juanjuan hoped to see – the landscape, people, food, and culture. What we also watch is a young woman who discovers herself, her deep reserves, and her emotional evolution as she goes from an young idealist with a dream to a modern heroine confronting all the tasks required to realize her quest.

What we don’t see is the vulnerable and iron-strong woman underneath, who sometimes received free meals simply from strangers recognizing her name, or went hungry for days while biking in the remote areas where the towns were hundred of miles apart. There’s also the narrative of the team members she took along with her, despite the fact she knew they wouldn’t make it from lack of strength and experience. Nonetheless, she funded these aspirants, despite the fact that “there was always the issue of money” until they gave up and went home, leaving her to plug on alone. Although we do see the woman who disguised herself as a man in order to stay at a worker’s camp, we can only guess at the struggle she had with one of her team members who pushed her for physical intimacy, despite the fact they were both married. When she rejected him, he broke two of her ribs. On three other occasions she got into fights with strangers to protect herself. Still, she continued to cycle. That internal dynamic woman drives this unforgettable and unrepeated story.

The most heartbreaking narrative ironically came at her triumphant return – when her husband told her he filed for divorce. For two months, Juanjuan collapsed from physical and emotional fatigue, developed a heart condition, and was nursed by her mother, who fed her “water one teaspoon at a time.” In Chinese tradition, a paper was applied to her face – to see if she still breathed. But her innate resiliency triumphed; six months later, Juanjuan mounted a photo exhibit of the trip at the Cultural Palace of Nationalities in Beijing.

Juanjuan lives to cycle; she is happiest on two wheels. She now seeks to bike around the world. This book testifies to her deepest belief: “We all have different abilities but we all have the same amount of time. Work hard and use your time well. Choose your own path, follow your own dream, - not mine. If you follow [somebody else], you won’t finish. Be determined, and you’ll make it.”

Sarah Massey-Warren

by Sarah Massey-Warren

From September 1987 through July 1989, Yu Juanjuan bicycled around the border of China and in the process changed Chinese women’s history. Starting from Beijing with four team members, three dropped out early, leaving her with only one-team member, Wang. For the majority of the 22 month trip she faced most of the diverse challenges – the demanding terrain, the reaction from natives of cities and villages she visited, the wildly fluctuating weather, the need for funding, and those arising from the fact that she was a young woman – alone. Since then, nobody has been able to duplicate her feat, man or woman. The strength of this remarkable woman’s story– a product of the intersection of Communist and modern China – result in a compelling richly illustrated book documenting the enormity of her success.

To understand the trip, one needs to know the unique qualities residing in the woman behind the journey. Juanjuan’s determination in envisioning and accomplishing the trip derive from her family background and upbringing, her own education and work experience, and an insatiable quest to see beyond the constraints of her own city. Her own parents were educated, lived on a university campus in Beijing, and had an 18” television that let in the world to a limited extent during the Cultural Revolution. “We had no news and no ads,” Juanjuan recalls. A young woman when Mao declared, “women hold up half the sky,” she came of age at a time of great upheaval and cultural change. With a job of her own and with her family’s encouragement Juanjuan had a strong desire for a future destined to be bigger than her grandmother’s bound feet. “Everybody thought I was crazy, not a real Chinese person,” she says of the reaction to her announcement to bike around the vast expanses of China. “A young woman is supposed to focus on husband and family – it’s your duty.”

But Juanjuan’s adventurous family genetics ran through her muscles and memory. Her father, a medical doctor at the Beijing Normal University, believed in her: “You’re bigger than that”, he said and encouraged her athletic daughter’s achievements. In fact, the men in Juanjuan’s family bequeathed a lust for travel. One grandfather owned a bookstore filled with books and photographs of the wider world. The other, her father’s father, joined the “underground army” at age fourteen, which allowed him to traverse the country. Although her mother, who worked in the university’s student office, was more traditional, she remained emotionally and financially supportive of Juanjuan and even more so after the trip.

A natural athlete, Juanjuan ran marathons and biked extensively. However, what really built the muscles and endurance for the journey came from the Cultural Revolution edict of mandatory farm work required of university students. Juanjuan spent two years doing heavy labor on a rural farm. Others urban teens did 10 years of mandatory farm work and some never made it back to Beijing. “I did the work of two men by myself,” Juanjuan recalls. Returning to Beijing in 1976 after Mao died, jobs were plentiful and she landed an office job in the sports department of the China People’s University. The job had other advantages – she had summer months at her discretion to bicycle to other universities, take free classes and take long bike trips. During that time, these preliminary bike trips became increasingly longer, and triggered her appetite to explore China’s circumference and all that lay therein.

“I wanted to get to know different cultures and religions, different ways of living, different clothes, ladies my age and know their dreams! I love cooking – I wanted to taste and try different food. I wanted a grand adventure and a way to get to know China myself first hand.”

Fortunately for the reader, Juanjuan is a shutterbug and a star in her own photos. Continually, she asked people to take pictures of her, despite the expense incurred for film and development. She collected stamps from the local government and post office at each village she visited, which verified the validity of her travels and her identity to strangers. The photo-journalistic narrative of people, landscape, and stamps takes us from Beijing to remote villages and large towns. Through the textual travels and stunning images, we see all that Juanjuan hoped to see – the landscape, people, food, and culture. What we also watch is a young woman who discovers herself, her deep reserves, and her emotional evolution as she goes from an young idealist with a dream to a modern heroine confronting all the tasks required to realize her quest.

What we don’t see is the vulnerable and iron-strong woman underneath, who sometimes received free meals simply from strangers recognizing her name, or went hungry for days while biking in the remote areas where the towns were hundred of miles apart. There’s also the narrative of the team members she took along with her, despite the fact she knew they wouldn’t make it from lack of strength and experience. Nonetheless, she funded these aspirants, despite the fact that “there was always the issue of money” until they gave up and went home, leaving her to plug on alone. Although we do see the woman who disguised herself as a man in order to stay at a worker’s camp, we can only guess at the struggle she had with one of her team members who pushed her for physical intimacy, despite the fact they were both married. When she rejected him, he broke two of her ribs. On three other occasions she got into fights with strangers to protect herself. Still, she continued to cycle. That internal dynamic woman drives this unforgettable and unrepeated story.

The most heartbreaking narrative ironically came at her triumphant return – when her husband told her he filed for divorce. For two months, Juanjuan collapsed from physical and emotional fatigue, developed a heart condition, and was nursed by her mother, who fed her “water one teaspoon at a time.” In Chinese tradition, a paper was applied to her face – to see if she still breathed. But her innate resiliency triumphed; six months later, Juanjuan mounted a photo exhibit of the trip at the Cultural Palace of Nationalities in Beijing.

Juanjuan lives to cycle; she is happiest on two wheels. She now seeks to bike around the world. This book testifies to her deepest belief: “We all have different abilities but we all have the same amount of time. Work hard and use your time well. Choose your own path, follow your own dream, - not mine. If you follow [somebody else], you won’t finish. Be determined, and you’ll make it.”

Sarah Massey-Warren